| UPDATES | GUEST BOOK | MEMORIES | MORE PICTURES | OTHER LINKS | BIBLIOGRAPHY | ||

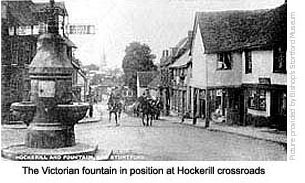

Drinking Fountain

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Markwell Pavilion

Also bordering the mound is the Markwell Pavilion and Elsie Barrett Club, given to the town by Frank Markwell in 1951 for use as a club for the elderly in memory of his wife, Elsie Barrett. One of Alfred Slapps Barrett’s three daughters, she later became the first woman Chairman of the Urban District Council.

Also bordering the mound is the Markwell Pavilion and Elsie Barrett Club, given to the town by Frank Markwell in 1951 for use as a club for the elderly in memory of his wife, Elsie Barrett. One of Alfred Slapps Barrett’s three daughters, she later became the first woman Chairman of the Urban District Council.

Unfortunately, the pavilion never fulfilled its potential and with little use eventually fell into disrepair. Its saviour was the town council, who in the mid 1990s decided to refurbished the property and open it as an all purpose facility for use by all residents of the town.

In 1999 the Salvation Army was also given use of the pavilion after attendances at their Portland Road home dropped so dramatically they were forced to sell the property (See Guide 14).

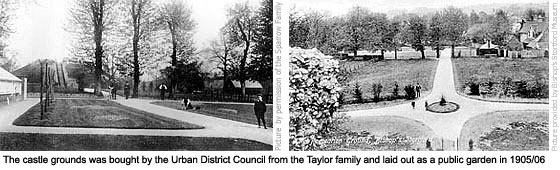

Castle Gardens

During the 19th century the castle mound and eight acres of surrounding land was owned by the Taylor family. In 1907 they decided to sell-up and instructed town auctioneers G E Sworders & Sons to handle the public auction. Before that happened, though, a specially created sub-committee had established that the owner, Mr F A Taylor, was willing to sell privately to the Urban District Council for £1,900.

During the 19th century the castle mound and eight acres of surrounding land was owned by the Taylor family. In 1907 they decided to sell-up and instructed town auctioneers G E Sworders & Sons to handle the public auction. Before that happened, though, a specially created sub-committee had established that the owner, Mr F A Taylor, was willing to sell privately to the Urban District Council for £1,900.

Wasting no time the council immediately arranged sanction to pay the asking price and closed the deal. What went on behind the scenes leading up to this point isn’t known, but council chaiman John L Glasscock is widely credited with obtaining this open space for the town.

The creation of Castle Gardens took place in 1907/08 when it was laid out with trees, flower beds, footpaths, fencing, bandstand and a shelter converted from an old cow shed. And as with all public spaces, bylaws were put in place: forbidding the public to beat their carpets or drive cattle through the gardens, or park perambulators on the flower beds.

Glasshouses once stood near to where the War Memorial now stands, used to produce flowers for these gardens, the cemetery gardens and for town occasions. The practise continued until the 1960s when the head gardener, Mr Forth, retired.

In 2011, tree experts advised that the avenue of 18 horse-chestnut trees linking the war memorial to Waytemore Castle motte should be felled. They were replaced in January 2012 by 22 tilla cordite ‘Rancho’ or small-leaved limes. Sadly, we now live in an age where there is an element in most communities who are intent on destruction. Many of the newly planted trees were vandalised or destroyed within days of planting. We can only hope those that remain are left to grow.

The War Memorial was unveiled on 3 April 1921 to commemorate the 207 men of the town who lost their lives in the First World War. It is said that the town of Bishop’s Stortford gave proportionally more of its manhood in that conflict than any other town in the Empire.

In May 1959, the advice of the Royal British Legion and the Imperial War Graves Commission was sought by Bishop’s Stortford Council on the idea of having the names of those who died in the Second World War inscribed on the memorial. The surveyor was also investigating the possibility of either inserting plaques at each corner of the memorial surround or on the stone extension of the base of the memorial. As is now evident, the names of the 107 local men and women who gave their lives were engraved on the base of the memorial, but not until the early 1960s.

The county emblems of both Essex and Hertfordshire are represented on two of the memorial’s sides, and each November on Remembrance Sunday a service is held here in memory of the fallen.

Close by, but easily missed, a triangular shaped memorial sits within a circular stone-surround in the middle of a flowerbed. This stone commemorates men of the local Masonic Society who lost their lives in overseas conflicts between 1843 and 1927. The main inscription reads ‘Write us as one who loved his fellow men’ and is credited to William Smith.

Close by, but easily missed, a triangular shaped memorial sits within a circular stone-surround in the middle of a flowerbed. This stone commemorates men of the local Masonic Society who lost their lives in overseas conflicts between 1843 and 1927. The main inscription reads ‘Write us as one who loved his fellow men’ and is credited to William Smith.

The privately owned bungalow adjacent to the War Memorial was originally built for Castle Garden’s head groundsman and stands on the former site of the 17th century Cherry Tree Inn, itself built on the site of the medieval gaol.

The Castle Gaol

Prisoners were originally kept in the castle dungeon, its earliest mention being in 1234 when Michael de Bentfield was ‘held in the King’s prison at Stortford’ for the death of Walter Galywon, and accused of breaking the King’s peace with violence and malice. All later reference is to the Bishop’s prison, built adjacent to the castle shortly after 1261 when the Statute of Lambeth ordained that every bishop had to provide himself with one or more prisons in his diocese (District). The gaol was better known as the ‘Bishop’s Hole’, and though felons from any parish in the bishop’s Liberty could be held here, it was mostly used as an ecclesiastical prison for convicted clerks.

Prisoners were originally kept in the castle dungeon, its earliest mention being in 1234 when Michael de Bentfield was ‘held in the King’s prison at Stortford’ for the death of Walter Galywon, and accused of breaking the King’s peace with violence and malice. All later reference is to the Bishop’s prison, built adjacent to the castle shortly after 1261 when the Statute of Lambeth ordained that every bishop had to provide himself with one or more prisons in his diocese (District). The gaol was better known as the ‘Bishop’s Hole’, and though felons from any parish in the bishop’s Liberty could be held here, it was mostly used as an ecclesiastical prison for convicted clerks.

Any clerk found guilty could only be punished by the bishop, who could degrade him or imprison him. A clerk was defined as such if he had the ability to read or write, or if his head was shaved – exhibiting the fact he had entered the priesthood or a monastic order. This exempted him from judgement by the King’s justice.

The size of the gaol is unknown but it was probably built to accommodate far less people than were usually held. In 1344 the prison population of 57 was gradually diminished when 29 of their number died, all of whom were buried within the prison grounds at a cost of one penny per burial. The following year there were 25 prisoners, of which 9 died.

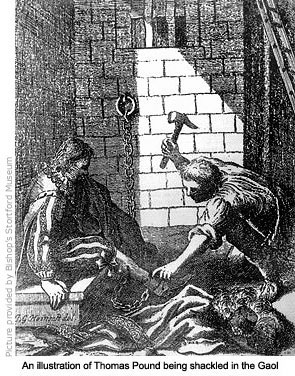

The gaoler’s accounts of 1347/8 reveal there were fifty prisoners and that one shilling (5p) a day was spent to feed them all. Conditions were appalling; prisoners generally kept chained to a wall or post in its ‘deep and dark dungeon’ infested with rats and fleas.

In 1388 an annual rent of three quarters of corn was given for the maintenance of the bishop’s prisoners by Bartholomew Vere and John, chaplains to the devout and zealous Robert Braybrooke, Bishop 1382–1401, whose coat-of-arms still appears on the tower of Much Hadham church.

The first English critic of the religious order, John Wycliffe, died in 1384 but his followers, known as Lollards, continued long after his death. In 1421 a number of them were imprisoned at Stortford but managed to escape. Afterwards, in a letter to Henry V, Bishop Clifford wrote that ‘perhaps one of the gaolers was in sympathy with their reforming zeal’.

In spite of all the precautions taken to retain prisoners, the gaol does not seem to have been that secure. In the early 1400s, batches of sixteen, eighteen and ten prisoners escaped in consecutive years. In the event of escape the king generally pardoned the bishop in office, but an exception to this rule occurred in 1429 when bishop William Gray was fined 640 marks (about £500) for his carelessness in letting five clerics escape. To add insult to injury they also took their jailer with them. Although much expense and time was spent in recapturing the men, the king allowed the bishop ten years in which to pay the fine.

Over the succeeding years countless men accused of heresy and other ecclesiastical offences were imprisoned in the gaol, but perhaps the worst time was during the Catholic rule of Queen Mary (1553–1558). Bishop Edmund Bonner was notorious for his inhumane treatment of political and religious prisoners and for many the only happy release from their terrible ordeal in his prison was death.

Thomas Pounde

During Queen Elizabeth’s reign the prison was used to hold Catholics, the most notable being Thomas [alias Duke, Harrington, Gallop, Wallop] Pounde (1539–1615), one time friend of the queen’s favoured courtier, Christopher Hatton (c.1540–1591).

Born in Belmont, Hampshire, to William Pounde, a wealthy landowner and his wife, Anne, the sister of Thomas Wriothesley, earl of Southampton, he was educated at Winchester and entered Lincoln’s Inn, London, in 1560. When his father died in 1564 he inherited extensive estates but squandered much of his new found wealth attempting to gain influence at court. For the same reason he conformed to the established Church. But in 1570, during twelth night celebrations at court, Pounde’s life changed direction. There, he directed plays, games and masques, some of which he wrote, but in an attempt to repeat an intricate dance step at the queen’s request, he fell. His embarrassment was furthered when Elizabeth ordered him to stand with ‘Rise, Sir Ox‘, to which Pounde muttered loud enough for others to hear, ‘Sic transit gloria mundi‘, and immediately abandoned the court for Belmont.

He then threw himself into prayer, mortification, almsgiving and charity, and after being impressed by the accounts of Jesuit missionaries, applied to join the society. Jesuits were known as the ‘Intelligence Service’, maintaining communications between England and Rome and devising plans of action against Protestantism.

England’s own Intelligence Service, however, were well aware of Pounde’s activities and when he arrived in London around 1574, in preparation to go to the continent, he was summoned by an official of the bishop of London and questioned regarding his religious beliefs. He was then jailed. His cousin, the earl of Southampton, secured his release from prison after six months, but only on condition he would remain in England at Belmont and not interfere with religious matters. Within a year he violated the latter condition and the bishop of Winchester jailed him at Winchester in 1576 for two months. From there he was sent to Marshalsea prison in London.

In 1578, while still in prison, he was secretly granted admission to the Jesuit society and in June 1580 received his vows as a Jesuit. He then petitioned the privy council for a public disputation on religious matters, saying that religious controversies could not be settled by scripture alone. On 18 September that same year, John Aylmer, bishop of London, sent him to the ‘lonely’ castle at Stortford, ‘for his own good and peace of mind’, and it was while incarcerated here that Pounde wrote to his friend, Christopher Hatton, describing the terrible conditions of the prison.

‘It is nothing but a large varst room, cold water, bare walls, noe windows, but lopholes too highe to loke out at, nor bed nor bedstead nor place very fit for any; the homeliest things a high pair of stockes, such a pair of virginalls (handcuffs) all athwart my cold harbor (dungeon) and nothing else but chains enough, which yet I am not worthy of’.

Pounde spent six months in Stortford’s gaol, and for the next twenty years was transferred from prison to prison: Marshalsea, Counter, Gatehouse, White Lion, the Tower of London, and Wisbech and Framlingham castles (with the exception of a period from approximately May 1585 until September 1586 when he was released on bail and restricted to his mother’s residence, first in Hampshire and then in Newington).

He was pardoned and released from Framlingham Castle when James I came to the throne in March 1603, but in late 1604 he was in trouble again after detailing the cruel sentences and punishment meeted out against Catholics by justices in Lancaster. For his criticism he was charged and found guilty of false accusation, the sentence being life in prisonment unless he conformed to the established Church. Only the intercession of Catholic ambassadors prevented much harsher punishment.

By early 1609, having spent half his life in prison for his beliefs, Pounde requested release from James I, and by June of that year was back at Belmont. What remained of his fortune was made over to his two nephews, both of whom he educated as Catholics although their parents were not. He also prepared himself to cross to a jesuit house on the continent, but his trip was ordered to be cancelled by his jesuit superior. He remained at Belmont where he died on 5 March 1615.

The prison was still in use up until the middle of the 17th century, although by this time the number of inmates had fallen dramatically. After Charles I was executed in 1649, Oliver Cromwell governed England as a Commonwealth and many changes were implemented throughout the land. Remaining prisoners at Bishop’s Stortford were transferred to the county jail at Hertford and the gaol and castle gatehouse demolished soon after.

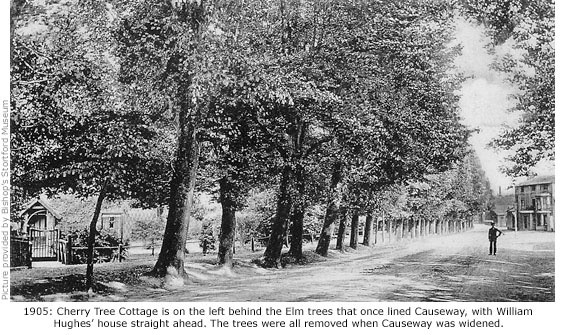

Cherry Tree Inn

Immediately after the prison was demolished, builders salvaged much of the stonework to build the Cherry Tree Inn on its former site. The inn’s name was a refreshing one after the misery that had gone before and was so named because of the numerous cherry trees that grew on the castle mound behind it.

Unfortunately, being so close to the moat the inn suffered constant flooding, resulting in much renovation and rebuilding and eventual closure in 1840. The property was then converted into a private residence owned by Edward Taylor and renamed Cherry Tree Cottage. But it still had no immunity to flooding and eventually just fell apart.

The remains were demolished in the 1930s and the site then used to build a house for the Head groundsman of Castle Gardens – the white bungalow that stands here now.

| LINKWAY | WAYTEMORE CASTLE | DRINKING FOUNTAIN | MARKWELL PAVILLION | CASTLE GARDENS |

| CASTLE GAOL | CHERRY TREE INN | CAUSEWAY | HOCKERILL CUT | HUGHES TIMBERYARD |