| UPDATES | GUEST BOOK | MEMORIES | MORE PICTURES | OTHER LINKS | BIBLIOGRAPHY | ||

Causeway

The small footbridge leading from Castle Gardens at this point was very likely the site of the castle gatehouse and drawbridge that gave access to the ancient causeway, and from which the present Causeway takes its name. In more recent times it extended as far as the former bridge in Bridge Street, but was curtailed at the time of town redevelopment in the early 1970s. In the Middle Ages reference was made to St Osyths Well, a natural spring in the Causeway close to the old town mill, the water of which was reputedly ‘good for the eyes’.

SEE ‘St Osyth’s Well’ AT FOOT OF THIS PAGE

Early local history books tell us that a ducking stool and stocks were sited in the Causeway up until 1745. Their exact site, according to a knowledgeable reader’s letter published in the Herts & Essex Observer, dated 1936, was close to the former moat where today there is the garden of Castle Cottage. Ducking stools came into general use as a form of punishment in the 17th century but were rarely used beyond the mid 18th century. Stocks, however, were still in general use up until the mid 19th century – though where the town stocks were moved to after 1745 isn’t recorded. Proof of their continued use, locally, is found in churchwardens’ accounts of 1824, recording payments to constables:

Putting a stranger in the stocks for being riotsome in the streets………..1s. 6d.

Placing James Warwick in the stocks for being drunk on the Sunday, help, etc……1s. 6d.

Keeping on the subject of criminal behaviour, an entry in the old minute books of the parish Vestry meetings tells us that in 1836 a public Vestry meeting was held ‘for the purpose of adopting measures for the erection of a cage, and to form a committee to carry the resolution into effect’. A cage was the forerunner to the police cell and generally used to hold drunks or the like until they sobered up. The ‘measures’ referred to involved finding out if the parish still had the right to use the existing cage, and to seek advice from the trustees of Sir George Duckett as to whether or not it could be positioned on ground that may have been in the ownership of the Stort Navigation, previously owned by Duckett.

Permission was seemingly given because the cage, originally positioned in North Street outside the George Inn then from 1718 outside the White Horse Inn, was eventually moved to Goosemead Green on a site later occupied by Hughes timber yard – now the site of the new Causeway development.

Goosemead Green was so named because it was where the Bishop’s geese roamed. And legend has it that in the reign of Queen Mary (1553–1558) the notorious Bishop Bonner burnt heretics at the stake on this land. This has since been disproved (See Guide 2), but it is perhaps because of this ‘story’ that this area was known in the 1930s as Martyrs Corner.

In 1775 the English evangelist and founder of Methodism, John Wesley, paid a visit to Bishop’s Stortford but was unimpressed with what he found. The town, he said, was ‘spiritually dead’. Had he still been around in 1823 he would have been pleased to witness the founding of the town’s Methodist community, and their first service held in the Causeway beneath the shade of a large elm tree. Present at that meeting was a Mr Anthony, Master of the original Workhouse at Hockerill (See Guide 9).

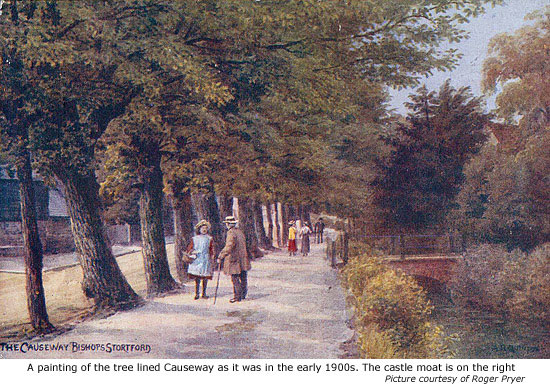

From the beginning of the 19th century until the time of town redevelopment in the 1970s, Causeway was lined with large elm trees. Their ample foliage formed a natural umbrella for many town events including, between 1901 and 1914, the annual Whit Monday Horse Parade – a magnificent display of working horses exhibited by local farmers, breweries and tradesmen. At the parade’s end, many of the horses would be taken to North Street and sold at auction (See Guide 6), but the event was finally brought to a close by the start of the First World War.

From the beginning of the 19th century until the time of town redevelopment in the 1970s, Causeway was lined with large elm trees. Their ample foliage formed a natural umbrella for many town events including, between 1901 and 1914, the annual Whit Monday Horse Parade – a magnificent display of working horses exhibited by local farmers, breweries and tradesmen. At the parade’s end, many of the horses would be taken to North Street and sold at auction (See Guide 6), but the event was finally brought to a close by the start of the First World War.

Between August 1914 and February of the following year, 20,000 troops from the North Midlands, en route to the battlefields of France, were billeted in and around the town. Many of the men were accommodated in private houses, schools and public buildings, but stables were at a premium and some 3,000 horses had to be kept at Causeway and in surrounding fields.

The very nature of the land here has always made this area prone to flooding and, prior to re-routing of the river across the Meads in 1969, Causeway always suffered the worst of the deluge. The problem was exacerbated by the castle moat running adjacent to the road. Engineering works by the river authority have since alleviated the problem but during the worst of winter weather, as was experienced as recently as 2000/01, there is no respite and Causeway is still the first to find itself under water.

Town redevelopment in the 1960s altered the once picturesque Causeway dramatically, for not only did the magnificent elm trees disappear but so too did many fine buildings and landmarks, including the town’s first swimming pool. Before 1924 townspeople had used a section of the river Stort near to Northgate End for bathing, but in that year an open-air swimming pool was constructed in Causeway, a gift of Mrs Tresham Gilbey in memory of her father, Sir John Barker, who died in 1915 (See Guide 7).

See also A History of Bishop’s Stortford Swimming Club.

The site of the pool now lays beneath the new Causeway development, but was close to where the library stands. This was opened in 1997 in a former frozen food store to replace the old library that stood next to it, built in the early 1970s. Prior to that this area had been the site of a large canal basin where barges journeying from London along the Stort Navigation would terminate.

Since the early 1800s, one of the most familiar and respected names in Bishop’s Stortford was Glasscocks; a building firm established for much of that time at Causeway in buildings that were once part of William Hughes foundry and timber yard. Sadly, Glasscocks, along with many other long established local firms, became victim of the Recession in the late 1980s and quickly went out of business. The firm did re-established itself in a much smaller form as Glasscocks Business Centre, and continued on part of the same site until 2004.

Also here until the Causeway development took place in 2005 was Adderley Road, a short stretch of road built in the early 1970s to link Riverside with Causeway, and named after Thomas Adderley who was instrumental in building the Stort Navigation.

Franklins Garage, established in 1928 by John Franklin, opened its first garage at Stansted Road and was partly housed in the former Red Lion Inn. In the 1930s the firm took premises in Hockerill Street and in 1981 moved to this much larger site on the corner of Adderley Road and Causeway. Franklins tenure here lasted until 1989 when they sold-up and returned to Stansted Road. But in June 2003, reorganisation by car-maker Renault led to this family-run firm losing its franchise and prompted Franklin’s to close their business for good, thus ending a 75 year-long association with the town.

The Jackson Wharf redevelopment project finally got under way in January 2005. Some townspeople protested, upset at seeing the demise of yet another part of ‘old’ Stortford, while others rejoiced, believing redevelopment of this area was long overdue. But as phase one of the £80m project now nears completion (2007) there have been complaints from the pro lobby as to the scale of the new development, particularly its six-storey height. Causeway has now been likened to looking like ‘New York’: the buildings over-bearing and totally out of character with what one should expect to find in an old market town. It has also now caused some concern as to what phase two of the development at Riverside might look like. We currently await a decision by EHDC’s planning department as to whether or not plans submitted by the developer should be changed.

It’s human nature to mourn the loss of old and familiar surroundings, but once gone many of us would be hard-pressed to describe what had actually stood on the site for so many years. For those who have already forgotten the shambles of buildings that made up Jackson Wharf and the eyesore that was the multi-storey car park, here are a few images to help jog the memory.

St Osyth’s Well

St Osyth’s Well in Bishop’s Stortford has always been something of a mystery. It is frequently mentioned in local history books, but all we are told is that the well was in the Causeway near to the old Town Mill and that its water was reputedly ‘good for the eyes‘.

Former town historian J.L. Glasscock was certainly aware of St Osyth’s Well, recording in his notes its position as 10 yards (9mtrs) from the river Stort and 20 yards (18mtrs) south-west of the old Town Mill. To be more exact, he said the well was in Jos Christy’s backyard. Joseph Christy was a tinsmith and brazier who opened a whitesmiths shops in 1854 adjoining the old Town Mill, which at time was designated as being in the Causeway. The site of that shop today would be approximately half-way between the Bridge Street entrance to Jackson Square and Devoils Lane.

Glasscock also noted that the well was in use up until about 1840, but that Christy filled it in and sealed off the right-of-way that previously led to it. Whether or not water from the well was still believed to be ‘good for the eyes’ at the time he filled it in is unknown, but there is mention of the water being good for the manufacture of pea soup! A later reference calls it Munday’s Well, but this could simply be due to a change of property ownership.

Having established where the well was sited, we now come to its name. Old English ‘osyth’ meant small stream; also, perhaps, a tiny watercourse or drainage channel. Locally this could be interpreted as a small tributary running off of the river Stort, or perhaps a drainage channel running into the Stort. There is reference to a medieval ditch running down the hill at this point, into the river.

But Glasscock also suggested the name might be eponymic – meaning the well’s title may have come from a character, person or ‘hero’, perhaps invented, in order to make it distinguished. This, and the fact that the well was reputedly ‘good for the eyes’ is a clue to its naming and possible origin.

In the Dark Ages, many such wells – or springs – with similar healing powers were to be found in Britain; named holy wells and mostly found close to abbeys, churches, monasterys and convents. One example is at Kemsing in Kent (near to Pilgrims’ Way), the remains of which is described thus: St Edith of Kemsing 961–984. This well lay within the precints of the convent where St Edith, daughter of King Edgar, passed her childhood. Hallowed by her presence its water became a source of healing, more especially the water was used to sooth eyes.

Water is, essentially, a prime necessity to life, and to early man a natural spring bubbling out of the ground, or from the crevice in a rock, would have appeared miraculous. Seemingly put there by the gods as sacred water it was thought to contain hidden curative properties for the sick and became a place of great sanctity. For this reason shrines were erected around springs and the great water spirit worshipped. The first Christian missionaries to these shores didn’t destroy these retreats dedicated to pagan divinity, but simply reconsecrated them to the protection of a Christian saint.

So if the waters of a well in Bishop’s Stortford had healing qualities – more especially for soothing the eyes – and was, perhaps, named St Osyth’s Well after a Christian saint; who was Saint Osyth?

Osith (latter day spelling Osyth) was a female English saint who is commemorated in the village of St Osyth in the county of Essex. The fact that Bede made no mention of this saint in his Ecclesiastical Chronicle doesn’t make her story any less believable, but certain aspects of it, as recorded by the 13th century chronicler *Matthew Paris (1200–1259), are most certainly legend.

The story begins in the 7th century in the village of Quarrendon (near Aylesbury), Buckinghamshire – at that time a part of Mercia – where Frithwald, a sub-king of Mercia in Surrey, and his wife Wilburga, daughter of King Penda of Mercia (d. 655 AD), had a daughter they named Osyth. She spent her childhood in a convent at nearby Aylesbury in the care of two maternal aunts, the holy abbesses, St Edith of Aylesbury and St Edburga of Bicester, and grew up with the ambition to be an abbess (Mother Superior) of an abbey or convent of nuns.

When St Edith died, Osyth was returned to her parents, but considering her far too important as a dynastic pawn to be allowed to further her religious ambition, they accepted, on her behalf, an offer of marriage from the King of Essex, Sigehere. He had relapsed into heathenism, but promised to embrace Christianity again on marrying Osyth. She, however, was set on a religious life and having already secretly taken the vow of celibacy, had no wish to be a queen. Her fate was sealed though, and after the marriage ceremony the pair departed for their honeymoon – possibly to London. In a desperate attempt to keep her celibacy vow, she made countless excuses to exclude the king from her bower – a separate house within the royal enclosure that she shared with her attendant ladies – but he finally managed to confront her.

As he did so, a cry went up from his lords that close to the gate of the royal residence was the largest stag that had ever been seen. The king’s passion for Osyth was immediately superceded by his passion for hunting and he and his court set off in pursuit of the stag. Osyth, regarding this interruption as the answer to her prayers, then ran away and sought the protection of Bishops Acca of Dunwich and Bedwin of Elmham. On his return, Sigehere discovered her whereabouts and on hearing the truth from his bride and the bishops, allowed her to take her religious vows and don the nuns habit. He then gave her part of his estate at Chich (now St Osyth) and built for her a church and a monastery where she fulfilled her ambition of becoming an abbess. The house was of the order of the Maturines.

But in October 653 AD the Danes were exploring our shores and a band of Vikings under Inguar and Hubba landed in the neighbourhood of Chich. After ravaging and pillaging the local area they eventually arrived at Osyth’s nunnery and took the young abbess into the Nun’s Wood where they commanded she renounce her religion and worship their own pagan gods. Despite threats of scourging and even worse torments she positively refused, so Hubba, incensed by his failure to dissuade her, struck out with his sword and severed her head. As it fell to the ground a fountain is said to have bubbled up from the earth where it lay, but Osyth rose to her feet, picked up her head and walked with it to the church of St Peter and St Paul, about one-third of a mile away. Only then did she collapse and die, falling against the closed church door and staining it with her blood.

There seems little doubt that Osyth was martyred, but the legendary ending has been somewhat embellished. The notion of somebody picking up their head after it had been severed may have been believable to ancient Britons, but we have to look for another explanation as to how she supposedly walked to the church after being dealt the fatal blow. A more likely explanation is that her head was not completely severed when the sword struck, but that her throat or neck was severely cut. Although still hard to believe, she may well have gathered all her strength to reach the church before collapsing and dying. There is also some descrepancy as to the date of her death, for although it seems generally agreed she was martyred on 7 October, the actual year ranges anywhere between 653 AD and 700 AD.

After the event Osyth is said to have been buried in the church of St Peter and St Paul at Chich, which she had founded, but with Danish marauders still threatening eastern England, her parents removed her body to St Mary’s church at Aylesbury. According to folklore, on the way to her final resting place they stopped at St James’s church in the village of Bierton, just outside Aylesbury, and there laid Osyth’s body upon a well at the rear of the church. Saint James is the patron saint of pilgrims, and the size of this impressive church does indicate it may once have been a place of great pilgramage.

MAP

The site of her martyrdom at Chich also became a shrine, with many ‘healings’ performed there, but on her removal to Aylesbury her martyrdom was transferred to the holy spring at nearby Quarrendon – her birthplace. Despite this, Osyth is said to have intimated, by visions and other signs, that she would prefer to rest at Chich. It is at this point that we come to yet another area of conradiction, because dates for this event also vary dramatically.

One source says that Osyth was returned to Chich just six years after her removal to Aylesbury, while another states that St Mary’s church became a site of great pilgramage until a papal decree in 1500 had her bones removed from the church and secretly buried elsewhere. This story cannot be verified because the Catholic Encylopaedia gave St Osyth no mention, basically because Bede gave her no mention in his Ecclesiastical Chronicle.

There is, however, a third account of her removal from Aylesbury back to Chich, which states it occurred ‘at some time’ before 1000 AD, and there, accordingly, she was eventually placed in a rich *shrine by Maurice, Bishop of London.

On the face of it, this would seem to be the one clue that links St Osyth with St Osyth’s Well in Bishop’s Stortford, for although her remains were buried at Chich long before it became a part of the Bishopric of London (1066), Maurice, Bishop of London (1085–1107) may well have been called upon to officiate at her enshrinement or done so of his own accord. In fact it seems likely it was the latter, because according to historian Pamela Taylor’s thesis on the Bishops of London estates (1976), Bishop Maurice was devoted to the cult of St Osyth. Such devotion gives every indication that he felt the need to honour her further, and so dedicated a well, or spring, to her memory in the one town that was of particular importance to him – Bishop’s Stortford.

There would of course have been countless wells and springs in the town at that time, but one that would never run dry would have been situated close to the river crossing, which was a haven for travellers. There is no evidence that Stortford became Hertfordshire’s medieval equivalent of Lourdes, but any spring that reputedly had healing powers would certainly have drawn many visitors.

With this in mind, a more cynical view might be that Maurice dedicated a well to St Osyth because he knew it would attract travellers and pilgrims, boosting the town’s popularity and, more importantly, its commerce. In fact, this view might be nearer the truth, moreso when you consider it was a bishop of London who gave permission for a town market here in the first place, no doubt because he saw the money-making potential of tolls and the renting out of sites to traders. It may even have been Maurice who sanctioned the market.

The water, of course, would have been no different to the water from any other well in the area, but medieval ‘marketing’ was as persuasive as modern-day marketing. Interestingly, the well was situated between Waytemore castle and St Michael’s church – *Saint Michael being the patron saint of sick people.

So if indeed bishop Maurice did dedicate a well, or spring, to St Osyth in Bishop’s Stortford, it would probably have been between 1102 and 1107 – the latter being the date of his death. A canon issued by Archbishop Anselm after the Westminster Council of 1102, ordered that no one should attribute reverence or sanctity to a fountain without the authority of a Bishop. Bishop Maurice didn’t need permission.

But this is all supposition, for without extensive research into ecclesiastical records or bishop Maurice’s private papers or will, assuming he made mention of St Osyth’s Well, his association with it cannot be proved.

The village of Saint Osyth in Essex, originally called Chich, takes its name from Osith, as do several other localities. This is one of the oldest places in the county and was once part of the Royal demesne of King Canute. He granted it to Earl Godwin, and he, by permission of Edward the Confessor, gave it to Christ Church, Canterbury. At the Conquest it was transferred to the Bishopric of London.

In the centre of the village, amid 383 acres of land, stands the medieval remains of the Augustinian priory of St Osyth, the building of which was begun in 1119 by the Bishop of London, Richard de Beauvays, or Belmeis (1108–1127), for regular canons of St Augustine at Chich, in honour of the great apostles, St Peter, St Paul and St Osith, virgin and martyre. Pamela Taylor’s thesis (1976) tells us there is a strong tradition that Bishop Richard was constrained to found the priory in penance for having tried to seize the property belonging to the canons who already attended the Saint’s shrine at nearby Clacton. St Osyth was the only house founded directly by a bishop of London and therefore got the most generous endowment.

It stands on the original site of Osith’s nunnery, which was probably destroyed by the Danes at the time of her murder. When Richard de Beauvays died in 1127 his remains were buried in the chancel of the adjoining church of St Peter, St Paul and St Osyth. He bequeathed the church and tithes to the canons, who elected as their first abbot or prior William de Corbeuil, afterwards Archbishop of Canterbury, who died in 1136.

At the Dissolution the Priory was surrendered to Henry VIII in 1539 by Prior Colchester and sixteen monks, and though it was given by the king to Thomas Cromwell, Earl of Essex on his attainder, it reverted to the Crown. Like the priory, the church is constructed of rubble and flints, and built mainly in the Late Perpendicular style, with portions of Early English and perhaps Norman styles. Both buildings are Grade 1 listed.

*In the late 17th century, reference to a well in Bishop’s Storford was also made by Celia Fiennes. The daughter of Nathaniel Fiennes, a Colonel in the Parliamentary army during the English Civil War, she is described as a nonconformist and a remarkable woman ahead of her time. Between 1685 and 1712, she (and two servants) travelled extensively around England on horseback, making notes in her journal of the many places she visited. Her notes, later published as ‘The Journeys of Celia Fiennes 1685–1712′, provided the first comprehensive survey of the country since King William’s Domesday Book, and have since been a valuable source of information of that period for historians. Her description of Bishop’s Stortford is brief, albeit complimentary, but she does make reference to a spring of water surrounded by a wall. There can be little doubt she is referring to St Osyth’s Well.

HERE BEGINS MY NORTHERN JOURNEY

IN MAY 1697 ffrom London to Amwell Berry in Hartfordshire 19 mile, thence to Bishops Startford in Essex 13 mile, w[hi]ch is a very pretty Neat Market town, a good Church and a delicate spring of Water w[hi]ch has a wall built round it, very Sweet and Cleare water for drinking. There is a little river runns by the town y[e]t feeds severall Mills.

*As a young man Matthew Paris had entered the monastery of St Albans. His interest in history soon gained him the position of assistant to Roger of Wendover, chronicler of the abbey at St Albans, and when he died in 1236 Paris took over from him. Paris gained much of his knowledge of the outside world from travellers who stopped over at the abbey, but has been criticised for relying too heavily on rumour and gossip. Despite this he is considered one of the most important historians of the period.

*Osith’s shrine at Chich is mentioned in the treatise ‘On the resting-places of saints’ (Attwater, Attwater2, Benedictines, Coulson, Walsh).

*More recently, Saint Michael has also become the patron saint of grocers, mariners, paratroopers and police.

*Saint Osyth is represented in art with a stag behind her and a long key hanging from her girdle, or otherwise carrying a key and a sword crossed, a device which commemmorates St Peter, St Paul and St Andrew. She is also depicted as a queen with her crown at her feet or on a table before her; sometimes carrying her severed head. She is venerated at Colchester. Her feast day is October 7.

| LINKWAY | WAYTEMORE CASTLE | DRINKING FOUNTAIN | MARKWELL PAVILLION | CASTLE GARDENS |

| CASTLE GAOL | CHERRY TREE INN | CAUSEWAY | HOCKERILL CUT | HUGHES TIMBERYARD |